The Common Ground

Between Theosophy and Judaism

A. D. Ezekiel

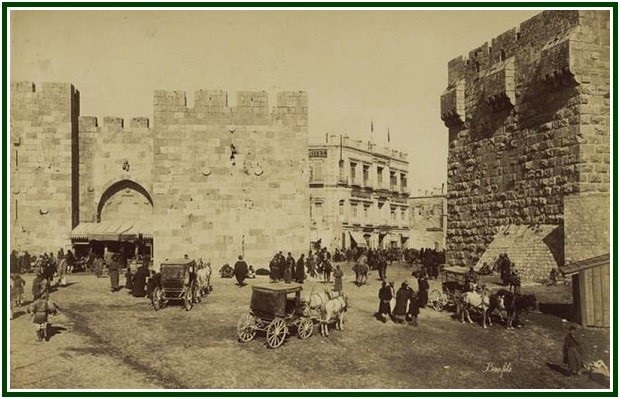

Jerusalem, the Jaffa Gate to the Old City, by 1899 (photo, Bonfils House)

A 2021 Editorial Note:

Abraham David Ezekiel joined the Theosophical Movement in India in the beginning of the 1880s. In the supplement of “The Theosophist”, August 1882, a note reports that Damodar Mavalankar went to Poona to recover his health from overwork, having been invited by A.D. Ezekiel to his home, in a drier and cooler climate. Damodar, who played a key role in the movement, spent one month in Ezekiel’s home. (See “Damodar”, comp. by Sven Eek, TPH, 1965, p. 285.)

On another occasion, H. S. Olcott – the first President of the Theosophical Society – made a visit to Ezekiel in Poona. (“Old Diary Leaves”, Third Series, pp. 306-308.)

When during the 1880s Emma Coulomb became an enemy of the theosophical movement and started fabricating lies against Helena Blavatsky as part of the Christian clergy’s campaign against Theosophy in India, the false texts prepared by Mrs. Coulomb aimed at involving Ezekiel in the anti-theosophical scheme. Mrs. Coulomb even tried to say that Blavatsky was not a friend of the Jews. More recently, Boaz Huss made a sad mistake in his otherwise useful text and research on A. Ezekiel, published in a 2010 book. Huss naively thought Emma Coulomb could be accepted as a source of historical information. In fact, Coulomb is well-known as a liar and Ezekiel did not support the attacks against Blavatsky and the movement.[1]

The Jewish theosophist Abraham D. Ezekiel appears in an 1882 photo with the main founders of the movement and other pioneers of modern theosophy. [2] In 1887 and 1888, he published various books on Kabbalah. His narrative “The Kabbalist of Jerusalem” is a valuable testimony on the common ground between Judaism and Theosophy.

(Carlos Cardoso Aveline)

000

The Kabbalist of Jerusalem

A. D. Ezekiel

While I am not at liberty to give the real name of the person whose remarkable experience in the search after occult truth is to form the subject of my present narrative, yet I may say that he is personally known to me as a Hebrew merchant of respectability and influence in one of the chief towns of Hindustan. As he is of the priestly caste of the Hebrews, I shall call him the Rabbi.

A native of Jerusalem, learned in our law, and in other respects well educated, he was nevertheless a thorough sceptic as regards the future life. As for magic, whether black or white, his attitude was one of scornful incredulity. The Kabbala, or mystical philosophy of our people, he regarded as little better than a jumble of obscure phrases and old wives’ fables. This was his mood of mind until his thirtieth year, when, at the Indian town above mentioned, a certain very striking circumstance befell him. He had to cross the river in a boat, and his attention was attracted to certain muttered threats made by a fellow-passenger at his side, who seemed greatly incensed at some third party not present, and unaware that he was speaking his thoughts aloud. An expression of malignity was upon his face, his features worked nervously, and between his clenched teeth, he said: “I will have my revenge! He wants to ruin me, does he? He would destroy my business and ruin my character? Well, we shall see what magic will do! He shall learn that there is a power that can crush him!” Saying so, he struck his knee with his fist, and in doing so unintentionally brought his elbow in contact with the person of the Rabbi. He instantly apologised for his rudeness, and this led to a conversation between the two.

“You will excuse my curiosity”, said the Rabbi, “but I overheard you make a remark just now which I cannot understand. Do you really mean to say that a gentleman of your apparent intelligence believes that there is such a thing as magic in this country of railways and telegraphs, and that it can employ powers to affect people for either good or bad?”

The man turned and looked at him in blank surprise. “Do you wish me to believe that you have any doubt upon that subject?”

“You really confuse me”, answered the Rabbi; “I never in my life met with a person who gave me to understand that he could entertain a belief – pray excuse me – so contrary as this to all the teachings of modern science, and, as it seems to me, of common sense, and I have scarcely words at command to answer your question.” “There is an Arabic proverb” rejoined the traveller: “If Naman teaches him not, Time will make him wise: have you sufficient curiosity about the subject to seek for proofs?”

“If my smattering of western education has made me sceptical in this direction”, said the Rabbi, “it has at least taught me the duty one owes himself, to shrink from no means to enlarge one’s knowledge.” “Then I shall take you just now to the place where I am going, and I warn you to be prepared for very novel experiences.”

The boat touched the opposite shore, the passengers disembarked, and the Rabbi’s new acquaintance led him to a distant street, where he at last stopped before a mud hut of most unpromising appearance. Bidding him wait his return, the stranger tapped at the door in a peculiar manner, and, upon a voice from within responding, entered and closed the door behind him. The Rabbi had not to wait long, for presently a shrill female voice called to him: “Open the door, Jacob, and enter.” The Rabbi had a shock of surprise at hearing his name thus pronounced in a strange town and by one of two persons of whom neither had any means of knowing his identity; but other and greater ones were in store, for, upon his obeying the invitation and pushing open the door, he saw sitting in Oriental fashion upon a piece of old matting upon the floor, a queer old woman, who began talking to him as familiarly about himself, his family and business, as though she had known him from boyhood. She told him whence he came, what had brought him to -, and what were his most secret beliefs respecting God, the soul, the future life, and magic. Her gaze fascinated him, for she seemed to be searching to the remotest corners of his memory; her eyes having a weird look as though gazing upon things behind the visible world.

Stunned by such to him unprecedented revelations of psychic insight, the Rabbi found himself in a state of mind the antithesis of his life-long scepticism: his whole fabric of materialism tottered, and he could only gaze, open-mouthed at the seeress, to the great amusement of his new friend, who laughingly asked him what he thought now of magic. The tension on his nerves became at last so strong, that he felt he must get away into the open air to collect his thoughts. Taking a hasty farewell of the seeress, who refused his proffered fee, and thanking his companion, he returned to his hotel, and spent a sleepless night in thinking over his adventure.

Various theories were tested and in turn rejected, and, since that of collusion was the least of all reasonable, in view of his identity being of necessity unknown to the other parties, he found himself in such a dilemma that he determined to seek the mysterious old woman once more and further test her powers. He did so, but his perplexity was increased by additional revelations. He came again, and again, no longer as a sceptic but as an eager enquirer. A new field of thought had opened before him, new and nobler ideas of man, of God, and of nature had presented themselves.

He felt a great yearning for knowledge, so great that it made him forget the paramount duties he owed to wife and children. The old seeress, however, recalled him to his senses. When he implored her to take him as a pupil, or, at least, show him where he could find a teacher, “Thy time”, said she, “is not yet come, Jacob: provide first for thy family, and then thou wilt be free to seek that mistress, knowledge, which tolerates no rival.” In vain he besought her to change her decision; her invariable reply was that his time was not yet come. Astonished to find a woman of such transcendental powers living in such squalor, he begged her to allow him to give her some comforts – a carpet to lie upon, a better mat, some new clothes to wear. She refused everything. “To the mind fixed upon the higher life, a scrap of course matting such as this is as pleasant as a silken carpet.”

One day, he asked her to show him some phenomenon of a physical character, to prove the control of the human spirit over the correlations of matter, “Shut thine eyes”, said she. He did so. “What seest thou, Jacob?” “A mist, pale grey at first, but now changing into a mass of colors. A landscape, now; a deep blue sky; a city with turrets and domes: it is – yes, it is Jerusalem, Dar-il-salam!” “What seest thou now?” “Our own street; my brother’s house, Ha! what is this? A precious MSS., a commentary upon the hidden meaning of certain biblical texts, that my late father – alloh haschalome! – most highly prized: it is in his handwriting. After his death my brother and I disputed for its possession; the case was referred to the elders, and they awarded it to my brother.” “Would’st thou know thy late father’s handwriting?” “Of course.” “Could’st thou be certain of the manuscript and know it from a forged copy?” “Most assuredly.” “And where seest thou that manuscript at this moment?” “At Jerusalem, in my brother’s house, in our father’s brass-bound box.” “Count seven, Jacob, and then open thine eyes.”

The Rabbi obeyed, and, to his consternation, saw lying before him upon the mat the identical manuscript he had just seen in the family house at Jerusalem! It was no copy but the very original itself, for it bore upon the last page a certain ink-blot that he himself had accidentally made when a child, by upsetting his father’s ink-horn, as he played upon the floor near his carpet. Whatever lingering shade of doubt there had been in his mind as to the reality of magic was dispelled by this last corroborative proof. And the MSS. is still in his possession.

Respecting the incidents of her life the old seeress was very reticent. “In the Divine Science, my son”, said she, “personality is forgotten if not obliterated: there is a new birth – that of the spirit, and the Kabbalist counts his age no longer from the nativity of the physical body, but from that second birth of the spirit. I am of thine own race, born at Constantinople, of a good family; thou may’st think of me under the name of Sarah.”

This was the Rabbi’s last interview with her. His business affairs brought him to Bombay where, for six weeks, he was my guest. Knowing my interest in Kabbalistical philosophy and theosophy, he engaged me daily for hours in conversation upon these subjects. He felt a peculiar interest in what I told him about spiritualism and mediumship, and night after night we used to sit together near the deserted bandstand, and talk about death and the future life until long after midnight had sounded from the clock tower. As he was going to Europe, I advised him to attend some séances of the more noted mediums, and he promised to do so. A few months later he wrote me from Paris that he had found the missing link in his chain of belief; at the house of a private medium at Paris a communication had been rapped out, giving the name and correct particulars about a friend of his who had died seven years previously.

From Europe he went to Jerusalem, and there made diligent enquiry for any living Kabbalist who would be able to give him instructions or direct his studies.

His researches were for a long time fruitless; the Rabbis proved to be mere formalists and worldlings, who derided his eagerness after such an “unattainable” knowledge as the Kabbala! But at last he heard that, in the synagogue Beth-el, situated in a remote quarter of the Holy City, and frequented only by the poorest Jews, there might daily be seen an eccentric old Rabbi who passed for a mad-cap. He was said to crouch all day in a corner of the synagogue, paying no attention to either the compliments or jibes of visitors. Some said he was a learned man; that, in fact, his mind had been affected by close attention to dream studies, while others, less charitable, set him down as a mere fool. The Rabbi Jacob’s experience with the seeress in India had taught him the useful lesson that appearances are, especially with mystics, often deceitful; so he went in search of the old recluse, and found him alone in the house of God after the congregation had dispersed.

Before addressing him he watched him from a distance. He saw before him a thin-faced, white-bearded old man, clad in a ragged national costume, and squatted upon a mat in the darkest corner of the synagogue. With eyes closed, he seemed alike insensible and indifferent to surrounding things. His appearance was not that of one asleep, but rather of one whose attention was fixed upon an inner world. A holy calm seemed to have settled over him, and this inward beautitude made Rabbi Jacob think he saw upon his face and round his head that Shechina, or soul-shine, which is believed to appear upon the face of the true seer; the brightness which overspread the face of Moses when he descended the Mount Sinai from the presence of God. It was with a reverence, then, that he approached the old man and uttered the salutation “Shalom e Alaichem!”

There was no reply, although the recluse opened his eyes, pushed back his sesceth, or head-veil, such as is worn by all Jews at prayer time, and looked vacantly at him. The visitor repeated the salutation with still greater deference. After a further short silence the mystic gave the usual response “Alaichem shalome!” but showed no desire for further conversation. The Rabbi then said: “May I have some conversation with you?” Whereupon the other fell to acting in a strange manner, trembling as if afraid, and, in a whining tone, said: “What have I done? What do you want of a harmless man like me? I know nothing about anything! ask someone else.”

The Rabbi reassured him as to his good intentions, and, mentioning the name of his late father, one of the best known Jews of the community, begged him to give him some information about the Kabbala. “Since you are the son of my benefactor, the good Rabbi Joseph, I will speak with you; but not here, such holy things must only be discussed in private. Tomorrow, at such an hour, come to such and such a street, and I shall tell you what you wish to know.”

The appointment was kept, of course, and our Rabbi was favoured with much information. Taking him by the hand, the recluse read his thoughts and answered questions that he had only framed in his mind. “You are not yet ready to begin the study of Kabbala”, said he; “you are not prepared. Your worldly interests occupy you. If your purpose is fixed, then it is not with me, you must begin your pupilage. Go to Tunis with this letter [and he handed him a note written in Hebrew and bearing a peculiar seal] and seek out a certain person whom you will find there engaged as a common laborer sprinkling the public streets, with others like him. They take this humble work for appearance sake, but they are Kabbalists, and they will teach you what you must learn before you come to Jerusalem as my pupil.”

In our long conversations at Bombay the Rabbi had learnt from me the leading facts about our Society, the alleged existence of the Himalayan adepts, and the teachings of the Aryan Sanathan Dharma about man and nature. These facts were all corroborated by the Kabbalist of Jerusalem. “There is but one God and one truth”, said he. “Whomsoever may be the teacher, he can but teach the Universal Doctrine. There are such adepts in the Himalayas, as there are others of the same kind in Egypt and other parts of the world. God has not abandoned any family of his children to their own ignorance and weakness. He would not be a true Father, if that were so. These doctrines promulgated by the Theosophical Society are identical with those taught by the Kabbalists of our race; there is the same rule of life, the same goal to reach. The world has never been without such teachers, nor will ever be. In the darkest night of superstition and ignorance, in the deepest depths of social degradation, there are always living witnesses to the truth. And now, my son, go in peace; and when thou art fully prepared thou mayst return to me.”

The Rabbi kissed the hand of the master, who laid it with a blessing upon his head, and then turned away and presently disappeared around the next corner of the street.

NOTES:

[1] See the book “Kabbalah and Modernity”, Aries Book, 2010, 482 pp., edited by Boaz Huss, Marco Pasi and Kocku von Stuckrad, pp. 167-182. In order to know more about the Coulombs – husband and wife – examine the extraordinary book “Helena Blavatsky”, by Sylvia Cranston. (CCA)

[2] See “A Photo From the 1880s”. (CCA)

000

The above text was published in the associated websites on 18 May 2021, being reproduced from “The Theosophist”, Adyar, Madras (Chennai), India, July 1887, pp. 597-601.

000

See the theosophical blog at “The Times of Israel”.

Read “Jerusalem, the Capital of Israel”, “The Universality of Temple Mount” and “Temple Mount as a Source of Peace”.

You might want to examine the text “Blavatsky, Judaism and Nazism”.

000