A Classic Review of the Main

Work in Raja Yoga Philosophy

Author Uncertain

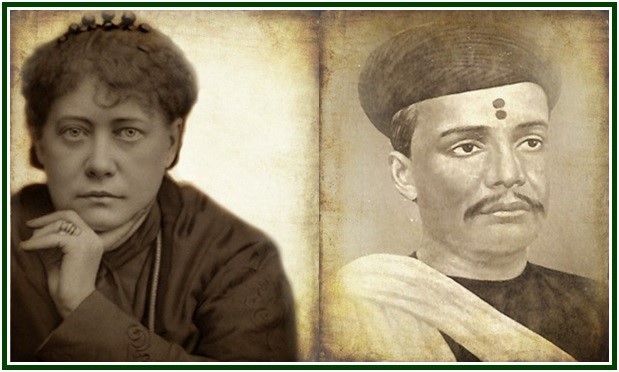

Helena Blavatsky and M.N. Dvivedi

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

A 2018 Editorial Note:

While there is no undisputable evidence about

the authorship of the following article [1], it is

certainly in harmony with Helena P. Blavatsky’s

views. H.P.B. had deep respect for Dvivedi’s

works, and she was the editor of the magazine

where this unsigned review was first published.

Sure, Blavatsky did not use to make personal praises

as the ones present in the first lines of the article, or in

its last paragraph. However, she did consider Dvivedi’s

writings significant. It is rather evident that she agreed in

general lines with this review. She may even have helped shape

parts of the article during editorial work. We don’t know about that.

(Carlos Cardoso Aveline)

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Our learned brothers Tookaram Tatya and M. N. Dvivedi have laid us under a fresh obligation, the one by publishing, the other by producing this new edition of the immortal work of Patanjali.[2] Without doubt it is the best edition yet presented to the English reading public, and will be welcomed by every Theosophist acquainted with one or another of the already existing translations and commentaries.

Following the good example of the arrangement by brothers Judge and Connelly, it dispenses with the annoying brackets of Govindadeva Shastri’s translation. But this is the least of its merits, for not only are the improvements in translation numerous, but the annotations of our learned professor follow with unvarying regularity each aphorism, written in an excellently clear style which will render the difficulties of the text, already considerably modified by Dvivedi in his translation, within the comprehension of every careful student.

The professor points out a fact that Western students are not sufficiently aware of, viz., that the study of Patanjali assumes an intimate acquaintance with the evolutionary system of the Sankhya philosophy of Kapila, which may be rendered as the numbering or analysis of the universe. The Yoga system adds the conception of Ishwara, or god, but whether Patanjali intended this term to connote a personal or impersonal deity is still a matter of dispute among the learned, in fact adhuc sub judice lis est. On page 94, Professor Dvivedi drops a useful hint in saying: “What Patanjali calls mind throughout is called Prakriti by Kapila”; this is a veritable Ariadne’s thread which will lead the steadfast enquirer to a remarkable discovery, for if the key to the apparently materialistic “atomism” of the Sankhya is once grasped, it will translate itself into the most spiritual and occult metaphysics the mind can conceive.

Generally speaking the annotation of this translation contains a large number of useful aids and suggestions for the student of occultism, especially with regard to reincarnation and the independent action of the mind. The idea of the supreme state attained by the Yogis is also well explained. It is called, in the Yoga-Sutra, Kaivalya and is “a state in which there is entire cessation of all desire, and when the nature of the essence of all consciousness is known, there is no room for any action of the mind, the source of all phenomena”. It is defined in the text as “the power of the soul centred in itself”, and further explained by the translator as “not any state of negation or annihilation as some are misled to think”. And he adds, “The soul in Kaivalya has its sphere of action transferred to a higher plane. . . . . . This our limited minds cannot hope to understand.”

It is impossible for all except the finest Sanskrit scholars to pass a sufficient criticism on the translation of the aphorisms, although a comparison with other translations will easily place Dvivedi’s in the front rank, both from the point of view of philosophy and comprehensibility. We shall, therefore, only remark on a few of the most salient points in the notes. Shraddha, which is translated by that scapegoat of a word “faith”, is thus explained:

“Faith is the form and the pleasant conviction of the mind as regards the efficacy of yoga. True faith always leads to energic action, which again, by the potency of its vividness, calls to mind all previous knowledge of the subject. This is energy which leads to proper discrimination of right and wrong.”

In commentating on the “Word of Glory”, the Pranava, the mystic Word OM, and its repetition, the annotator says:

“Japa means repetition, but it should be accompanied by proper meditation on the meaning of the words or syllables repeated. The best way is Mânasa, i.e., mental, such that it never ceases even during work, nay, even in sleep.”

Verb. sat. sap.! The 40th and following aphorisms of Book II deal with “purity” and it is interesting to remark how these spiritual sciences of old insisted on “mental” purity as of the first importance. How little has the solitary hint, “he that looketh on a woman to lust after her, hath committed adultery already with her in his heart”, been understood by the West! And how desperately we need the knowledge of such elementary facts of Eastern occultism, and the Gupta Vidya, is known but too well and miserably by all Western students. The “unco guid” scowl at Tolstoi, when he points to the knot that is choking them; still they will have to get their fingers on it some day if they do not wish to be “cast out into the swine”.

The very difficult and obscure aphorisms IX et seq., Book III, are explained more intelligently than heretofore. After explaining Nirodha as meaning “the interception of all transformations, or thought and distractions”, and further elucidating that these distractions are not those ordinarily understood, but “the distraction which is still there (sc., in the mind), in the form of Samprajnâta or conscious Samâdhi, the result of Samyama” (i.e., the union of the three processes: Dhâranâ, contemplation, or “the fixing of the mind on something external or internal”; Dhyâna, the making of the mind one with the object thought of; and Samâdhi, the forgetting of this act and the becoming one with the object of thought) – he says:

“The moment the mind begins to pass from one state to the other (sc., from conscious to so-called ‘unconscious’ trance), two distinct processes begin, viz., the slow but sure going out of the impressions which distract, and the equally gradual but certain rise of the impressions that intercept. When the intercepting impressions gain complete supremacy, the moment of interception is achieved, and the mind transforms itself into this intercepting moment, so to speak. It is in the interval of this change that the mind may droop and fall into what is called laya or a state of passive dulness, leading to all the miseries of irresponsible mediumship.”

He reiterates this “warning” again in another passage when saying: “Mere passive trance is a dangerous practice, as it leads to the madness of irresponsible mediumship”; and again in describing the four Yoga states, he says:

“When the Yogin passes from the first state and enters the second, his danger begins. He is en rapport with those regions that are not amenable to ordinary vision, and is therefore open to danger from beings of that realm, good, bad, and indifferent. These are called Devas – powers of places, i.e., powers prevailing over various places or forces, such as residence in heaven, company of beautiful women, &c. . . . . But besides these temptations, either seen or unseen, there may be various other ways, both physical as well as spiritual, in which the aspirant may be worried, frightened, or anyhow thrown off his guard, and tempted or ruined. The only remedy for all this mischief is supreme non-attachment, which consists in not taking pleasure in the enjoyment of the temptations, as well as not taking pride in one’s power to call up such. A steady calm will carry the Yogin safe to the end. If this cannot be done, the very evils from which the Yogin seeks release would harass with redoubled strength.”

Oyez, Oyez, ye psychics!

In annotating the XVII aphorism of the same Book, Professor Dvivedi gives us a very interesting exposition of the Sphota doctrine.

“Sphota”, he says, “is a something indescribable which eternally exists apart from the letters forming any word, and is yet inseparably connected with it, for it reveals (Sphota, that which is revealed) itself on the utterance of that word. In like manner the meaning of a sentence is also revealed, so to speak, from the collective sense of the words used.”

So also with nature sounds, cries of animals, &c. By a knowledge of the Tatwas and the practice of Samyama, the yogin can sense all sounds; this is one of the Siddhis or “powers latent in man”.

The appendix contains some selections from the Hathapradipikâ which deals with the practice of Hathavidya, that is Hathayoga, of which the less said the better. The diet recommended, however, may be useful to Vegetarians. It is: “wheat, rice, barley, milk, ghee, sugar, butter, sugar-candy, honey, dry ginger, five vegetables (not green), oats and natural waters”. This puts us in mind of another interesting passage in the notes on aphorism XXX Book II, which enjoins forbearance from five evils, and is almost identical with the Buddhist Pansil. The word himsâ is translated, for want of a better term, “killing”, and thus explained:

“It means the wishing evil to any being by word, act, or thought, and abstinence from this kind of killing is the only thing strongly required. It obviously implies abstinence from animal food, inasmuch as it is never procurable without direct or indirect himsâ of some kind. The avoidance of animal food from another point of view is also strongly to be recommended, as it always leads to the growth of animality to the complete obscuration and even annihilation of intuition and spirituality. It is to secure this condition of being with nature and never against it, or in other words being in love with nature, that all other restrictions are prescribed.”

This is further explained in the note to aphorism XXXV, where it is said:

“The abstinence here implied is not the merely negative state of not killing, but positive feeling of universal love. . . . . When one has acquired this confirmed habit of mind, even natural antipathy is held in abeyance in his presence; needless to add that no one harms or injures him. All beings, men, animals, birds, – approach him without fear and mix with him without reserve.”

Finally, if any one raise the question “cui bono; what good can such books do to us Westerns”; they will not have far to seek. We have already heard threatening rumours that some of our best minds, who have been fed solely on the intellectual husks of modern research, have raised the cry, “there is no scientific basis, no raison d’être for ethics; all such unscientific garbage is hysterical emotionalism”. The ancient soul-science of Aryavarta gives such objectors the “lie direct”. As well stated in our thoughtful and learned pundit’s introduction:

“A system of ethics not based on rational demonstration of the universe is of no practical value. It is only a system of the ethics of individual opinions and individual convenience. It has no activity and therefore no strength. The aim of human existence is happiness, progress, and all ethics teach men how to attain the one and achieve the other. The question, however, remains, what is happiness and what is progress? These are issues not yet solved in any satisfactory manner by the known systems of ethics. The reason is not far to seek. The modern tendency is to separate ethics from physics or rational demonstration of the universe, and thus make it a science resting on nothing but the irregular whims and caprices of individuals and nations.”

“In India, ethics have ever been associated with religion. Religion has ever been an attempt to solve the mystery of nature, to understand the phenomena of nature, and to realise the place of man in nature. Every religion has its philosophical as well as ethical aspect, and the latter without the former has, here at least, no meaning. If every religion has its physical and ethical side, it has its psychological side as well. There is no possibility of establishing relations between physics and ethics, but through psychology. Psychology enlarges the conclusions of physics and confirms the ideal of morality.”

This “missing link” will be found everywhere in Manilal Nabhubhai Dvivedi’s book, and we are delighted to congratulate both him on his work, and also those who will be fortunate enough to be persuaded to study this valuable contribution to Theosophical literature.

NOTES:

[1] Original title: “The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali”. First published at the London magazine “Lucifer”, February 1891, pp. 509-512. The word “Lucifer” is a pre-Christian, Latin term meaning “light-bringer”. The word refers to the planet Venus, the morning star, and has been grossly distorted by Christian priests. (CCA)

[2] “The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali”, Translation, with Introduction, Appendix, and Notes, based upon several authentic Commentaries, by Manilal Nabhubhai Dvivedi, sometime Professor of Sanskrit, Sâmaladâsa College. Click to see the book in one of our associated websites. First published by Tookaram Tatya for the Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund, 1890. (CCA)

000

See the book “The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali”.

000

The article “The Yoga-Sutra in Dvivedi’s Version” was published in our websites on 28 August 2018.

000

Read the book by William Q. Judge entitled “The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali”.

You might like to see the articles “Experiencing the Yoga Aphorisms”, by Carlos Cardoso Aveline; “The Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali”, by Katherine Hillard; and “Reflections on Patanjali’s Yoga”, by The Theosophical Movement.

000